🏛️Henry Singleton: The Greatest Capital Allocator in American Business

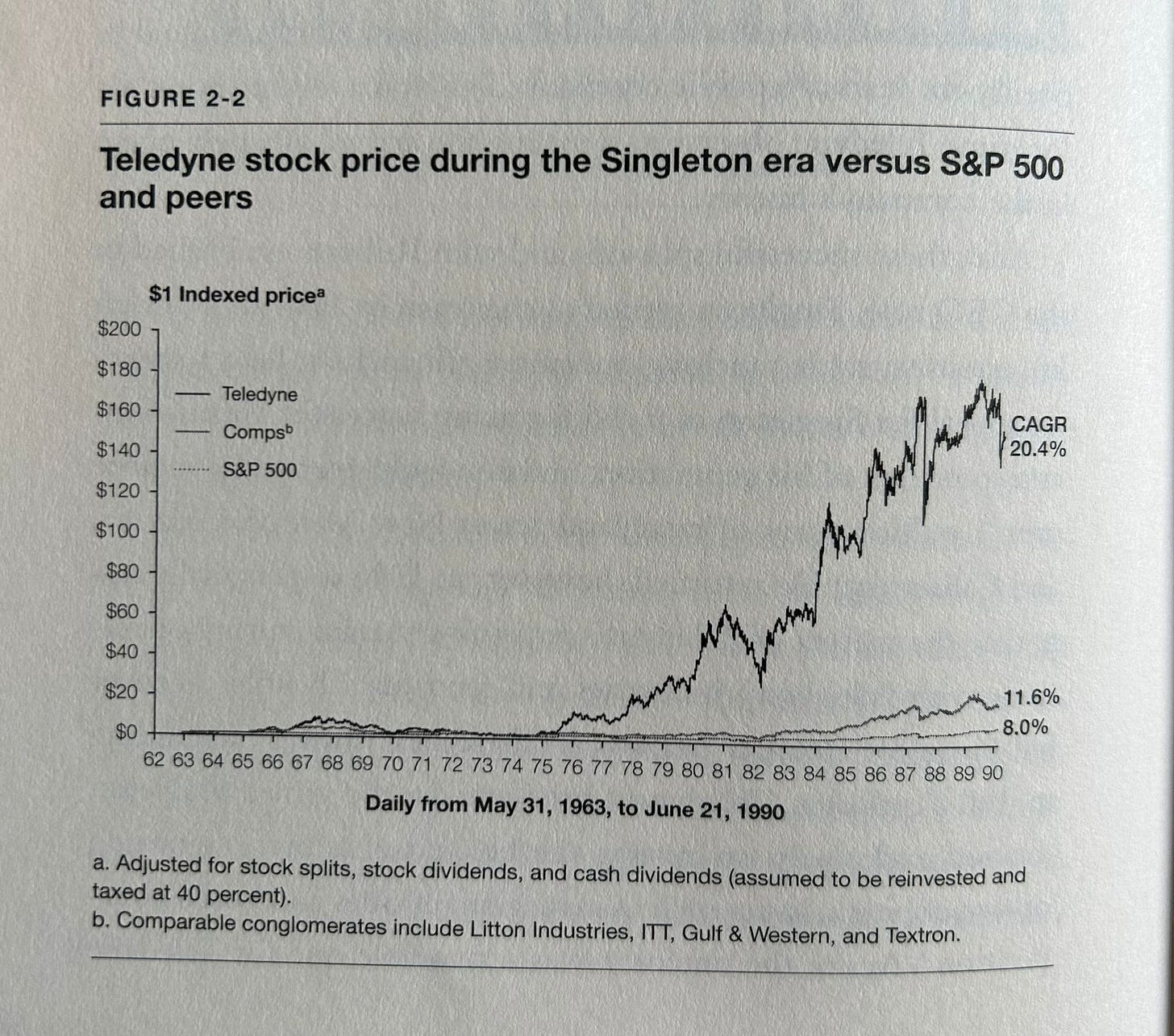

From 1963 to 1990 Henry Singleton delivered an astonishing 20.4% compound annual return to shareholders, vs 8.0% for the S&P 500 over the same period.

In 1960, Henry Singleton co-founded Teledyne, a conglomerate with companies in industries ranging from aviation electronics to specialty metals and insurance.

From 1960 to 1990, Singleton ran the conglomerate, generating remarkable results and thus cementing himself as one of the greatest capital allocators in history.

Early days

Singleton was born in 1916 in Haslet, Texas. He was an exceptional mathematician who attended MIT, earning bachelor’s, master’s and PHD degrees in electrical engineering.

Upon graduating, Singleton had a stint at North American Aviation and Hughes Aircraft as a research engineer and Litton Industries as a general manager, before co-founding Teledyne alongside George kozmetzky and a $450,000 initial investment.

Teledyne began by acquiring three small electronic companies and successfully bidding for a large naval contract. The following year, in 1961, they became a public company.

Acquisition frenzy

In the 60’s, conglomerates were the Internet stocks of their day, trading at very high prices. Many took advantage of these prices and swallowed up any business they could get their hands on, using their high stock prices as funds. These acquisitions brought more profits, higher stock prices, which were then used to buy more companies. The cycle continued.

Singleton took advantage of Teledyne’s high stock price during this period (which ranged from a P/E ratio of 20 in 1961 to 50 in 1969), by building a diversified portfolio of businesses.

Between 1961 and 1969, he acquired 130 companies.

Although Singleton partook in the acquisition frenzy of the 60’s, his process differed from that of others. He did not buy indiscriminately.

When buying companies, Singleton focused on profitable, growing companies with market leading positions.

Additionally, he refused to pay more than 12 times earnings when acquiring companies. This was in contrast to other conglomerates who would buy companies for high earnings ratios, without any proven earnings ability.

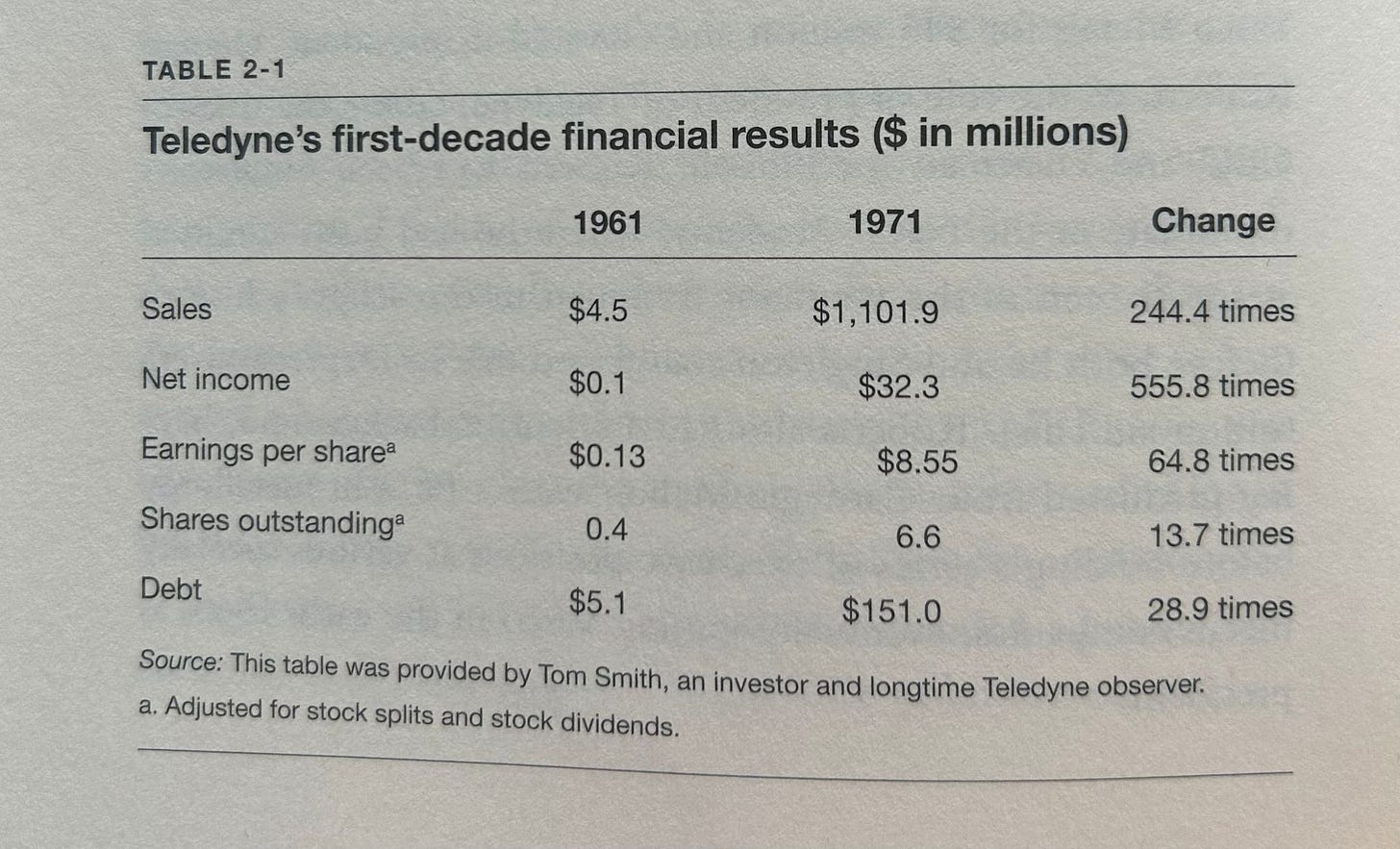

Here’s an overview of just how much value Singleton created in the first 10 years of running Teledyne, during his acquisition frenzy:

When the music stops

The thing that made Singleton so great was his disciplined independent thinking, that allowed him to change his mind and not follow the crowd.

Singleton famously told a Business Week journalist that his only plan “is to keep coming to work everyday”. He claimed he never had a long term business plan for Teledyne, giving him the flexibility to react to market conditions.

I change my mind when the facts change. What do you do?

-John Maynard Keynes

In the late 60’s many of the big conglomerates began to miss Wall Street’s earnings estimates, causing their stock prices to drop.

When the multiple on Teledyne’s stock dropped, and acquisition prices began to rise, Singleton abruptly stopped acquiring business, dismissing his acquisition team.

He knew that with a lower P/E ratio, it was not attractive to use his stock to buy other companies.

A Culture of Accountability

Singleton ran his conglomerate very differently to his competitors.

Many conglomerates had fancy headquarters, sprawling with executives, planners, and advisers etc. Henry Singleton hated the idea of this, and instead wanted to drive accountability right down the chain.

Teledyne ran an extremely decentralised operation, breaking the company into small parts and giving managers autonomy to run their respective businesses.

This set-up is similar to that of Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, where he gives full operational ownership to the managers of his businesses, as he understands that they know best about the day-to-day operations.

The Focus on Existing Operations

After Singleton stopped acquiring businesses in the late 60’s, he began putting his focus on existing operations.

The typical CEO sets their business up to please Wall Street, by optimising reported earnings. Not Singleton. He didn’t even engage with Wall Street analysts, seeing it as an inefficient use of time.

Instead, he focused on what mattered to shareholders and set up the company to maximise free cash flow, building Teledyne’s war chest.

Our accounting is set to maximise cash flow, not reported earnings.

-Henry Singleton

The focus on cash flow also set the basis for bonus compensation for all business unit managers.

Teledyne’s margins quickly improved, as working capital dramatically reduced. Additionally, throughout the 70’s, Teledyne’s operating businesses averaged north of 20% for return on assets.

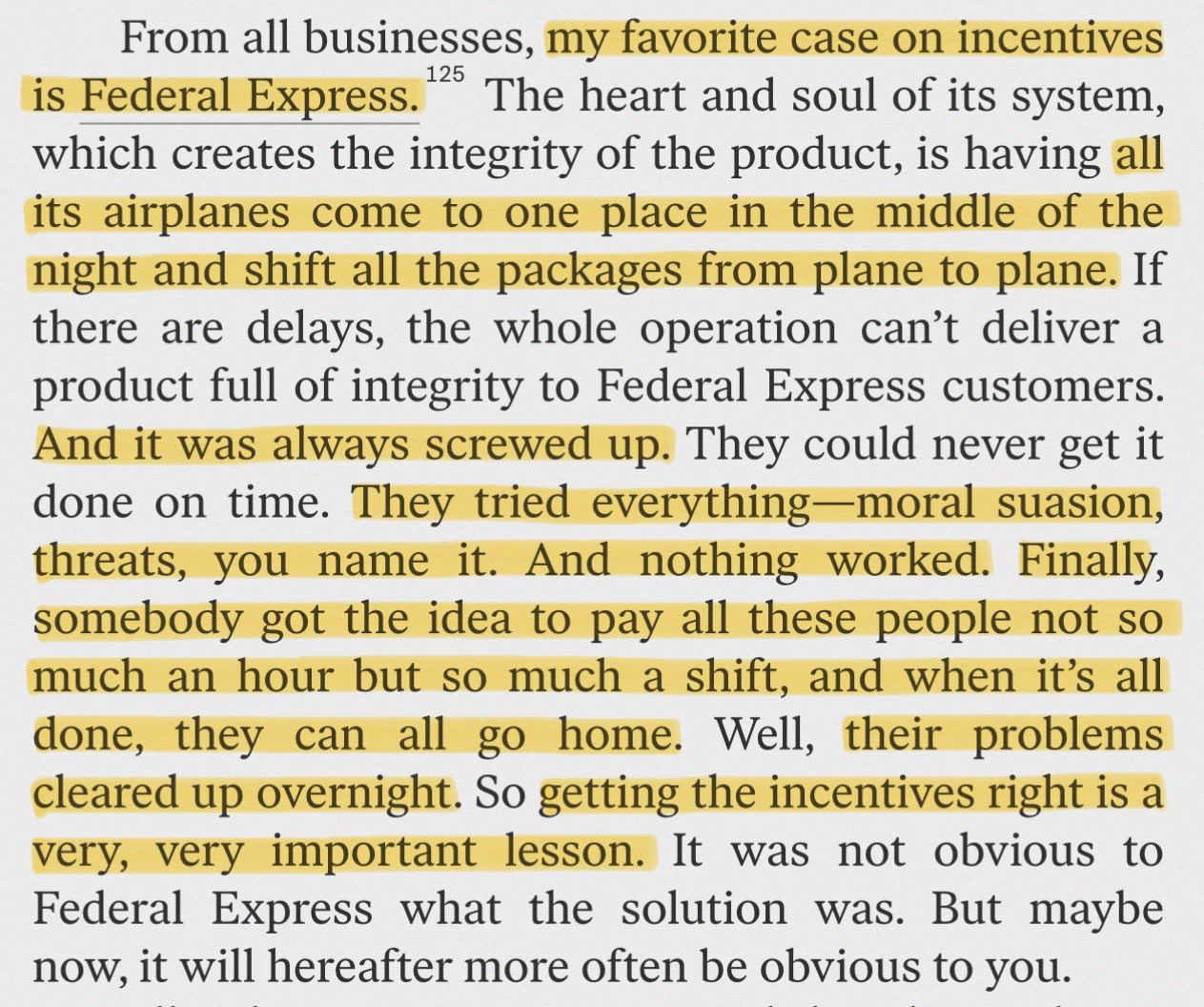

Case Study: The Power of Incentives

Singleton’s idea to eschew Wall Street earnings and instead focus on free cash flow generation was an impressive example of independent thinking and being a contrarian.

However, I think the more impressive part of this idea is how he used this cash generation focus as an incentive for bonus compensation. It seems Singleton knew the power of incentives.

Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome.

-Charlie Munger

Here’s another great example of the power of incentives and how important they are to get right:

Becoming a Cannibal

In 1972, with a large war chest of cash and acquisition prices still high, Henry Singleton made a call to one of his board members, Arthur Rock:

“Arthur, I’ve been thinking about it and our stock is simply too cheap. I think we can earn a better return buying our shares at these levels than by doing almost anything else.”

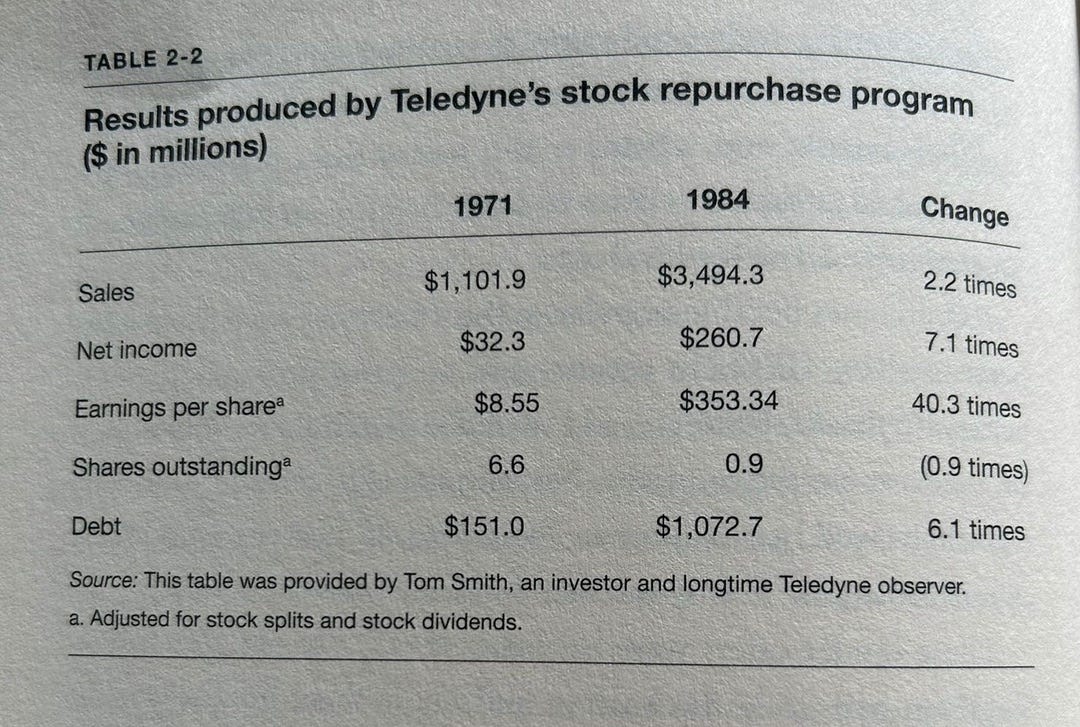

From 1972 to 1984, through 8 tender offers, Singleton spent $2.5 billion buying back 90% of Teledyne’s outstanding shares!

Across the 8 separate tender offers, Singleton generated a 42% compounded annual return for Teledyne’s remaining shareholders.

Additionally, across the buyback period, Teledyne’s EPS increased by fortyfold.

Nowadays, many CEO’s will roll out buyback programmes which involve setting aside a small percentage of cash flow to buy shares over a set period of years. This approach likely doesn’t have the biggest impact on long-term shareholder value.

Sinlgeton’s approach however was one which was bold and had a clear impact on shareholder value. On one occasion alone, when Teleydne’s earnings ratio was near an all-time low, Singleton initiated one of the largest tenders, which resulted in him buying over 20% of outstanding shares.

There is a reason why he is called the Babe Ruth of buybacks in Willian Thorndike’s book The Outsiders.

You can see below the dramatic increase in earnings per share over the buyback period, as Singleton bought over 90% of outstanding shares, leaving remaining shareholders with a greater percentage of ownership and share of the earnings pie.

Portfolio Management

In the mid-70’s Singleton took on direct responsibility for investing the stock portfolio’s of Teleydne’s insurance subsidiaries.

This gave Singleton the opportunity to put his insurance companies’ ‘float’ to work, which is the money held by insurance companies by selling premiums that has not yet been paid out to claimants.

When it came to portfolio management, it is no surprise that Singleton was a contrarian in this space too.

In 1975, when Singleton took over direct responsibility of the insurance portfolios, the total equity allocation was around 10%.

By 1981, the equity allocation in them had increased to 77%. This was during a period of a severe downturn in the market, where Singleton knew lots of equity bargains could be found.

In addition to increasing his portfolio’s exposure to equities, he also bet big on single companies. At one point, five companies represented over 70% of his combined equity portfolio, with 25% allocated to one single company.

Henry Singleton’s concentrated investment approach was similar to that of Buffett and Munger, who tend to bet big on things they know and understand well.

Portfolio concentration may well decrease risk if it raises, as it should, both the intensity with which an investor thinks about a business and the comfort-level he must feel with its economic characteristics before buying into it.

-Warren Buffett

Deconglomeration

In the words of board member Fayez Sarofim, Singleton knew “there was a time to conglomerate and a time to deconglomerate”.

Toward the latter period of Sinlgeton’s time running Teledyne, he began spinning off companies.

In 1986, and then in 1990, Teledyne spun off its insurance companies Argonaut and Unitrin respectively. The idea was to reduce complexity of the conglomerate, but more importantly unlock the full value of the subsidiaries for shareholders.

The Scorecard

Singleton had an incredible run leading Teledyne, producing returns that dwarfed that of his peers and the market.

From 1963 to 1990, Singleton delivered a 20.4% compounded annual return, compared to 11.6% for peers and 8.0% for the S&P 500.

$1,000 invested in Teledyne in 1963 would have grown to just under $180k by 1990.

There are clearly some incredible traits and virtues that Singleton displayed that we as investors can look for when deciding to invest with superior management.

These include the ability to shrewdly allocate capital with shareholder interest in mind, being able to think independently, having the flexibility and humility to change ones mind, and being able to understand and deploy the power of incentives.

Acknowledgement

The Outsiders by William Thorndike was the primary source for this post. I would highly recommend this book - it is a great bit of reading on successful CEO’s.